He played for one day, he played for another, he played for yet a third

Research

Presentation at the second symposium for folk music researchers, Helsinki, 28 November 2016.

Arja Kastinen

(English translation: Sara Norja)

Karelian kantele improvisation

It is bewildering to notice how the actions of a single person can sometimes have a crucial effect on future developments. A hundred years ago, in the summers of 1916 and 1917, the young researcher of folk music, Armas Otto Väisänen, travelled to Border Karelia (beyond the current Russian border, the Northern parts of Ladoga Karelia, and some parts of North Karelia in present day Finland) to collect tunes. He came back with 520 tunes, of which 134 are kantele tunes. (Timonen 2011, 193.) Something very significant came about because of the travels of those two summers when Suomen Kansan Sävelmiä V, Kantele- ja jouhikkosävelmät (Finnish Folk Tunes V: Kantele and Bowed Lyre Tunes), edited by Väisänen, was published in 1928. This book introduces the archaic kantele tradition that was part of the runo song culture; this tradition had already disappeared from most parts of Finland by the time of publication. The book includes musical notation for the tunes, and a detailed discussion of playing technique, tuning practices, and the scales used. Most impressively, there are also individual discussions on many musicians’ personal playing styles. As the decades passed and history, wars and Finland’s changing borders had their effect, this archaic style of kantele playing disappeared entirely from the region of Finland.

In 1980, in the second issue of the Finnish folk music magazine (Kansanmusiikkilehti), Heikki Laitinen published a wide-ranging article titled Karjalainen kanteleensoittotyyli (‘The Karelian kantele playing style’), which analysed this playing style. In addition to an in-depth discussion of the subject, what emerges as interesting for the present-day reader are the following sentences from the article: “I focus on the material from Border Karelia also because I believe it retained many features not only from Karelian, but from ancient Finnish kantele playing styles in general. At the same time, I hope that my description might prove to be an inspiration for someone to learn this interesting playing style.” (Laitinen 1980, 45.) The first of these sentences has formed the basis for my own research.

Concerning Laitinen’s second sentence, it will suffice for me to note that in the past decades the situation has changed dramatically – nowadays, this archaic style of kantele playing can be studied in our country’s only university for music as well as in e.g. several music schools and conservatories around the country. Without the material collected by Väisänen in 1916 and 1917, the new emergence of this tradition would not have been possible. To quote Senni Timonen: “The continuing and deepening renaissance of this archaic kantele playing style in Finland has taken most of its learning and inspiration from this book.” (Timonen 2011, 194.)

Most of the kantele tunes recorded by Väisänen in 1916–1917 represent the dance music of their time from Border Karelia–i.e. the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. The most typical of the Russian-based dances are the ristikontra and maanitus: their final sections include the ripatška (i.e. brisatka, ristakka, prišonkka, tripatška etc.) together with its siiputus. In Asko Pulkkinen’s book Suomalaisia kansantanhuja (‘Finnish Folk Dances’, 1946), he records Andrei Vilga mentioning that in Suistamo in 1914, the ristakondra (i.e. ristikontra) was still a common dance, but the maanitus was disappearing. In Suistamo, people also danced the hoilola and kiberä dances, collected from kantele players. According to Asko Pulkkinen, these dances had spread from the east along the shores of Lake Ladoga all the way to Sortavala. Before their arrival, people in Sortavala had danced dances that came from the west, such as the markkoa or laputus. These dances used to be common up to the 1870s, until the new dances, the ristikontra and the riivattu arrived from the east. (Pulkkinen 1946, 10 ja 104.) Also e.g. waltz and polka tunes were collected from some of the musicians. Thus, these recorded dance tunes do not represent ancient music.

My interest is, then, focused on the way in which these tunes were played; on the build-up of the music with constant small-scale variation, and tuning the instruments according to fourths and fifths; the special playing technique, and especially the musical texture evident in the kantele music which is more archaic than the most common dance tunes in the early 20th century. I am also interested in the resonance caused by interval relationships and the building of the musical texture along intervals rather than chords; the constant melodic and rhythmic variation; a musical, flaming world, inside which the musician seemed to sink.

Some of the kantele players recorded by Väisänen belonged to an older, illiterate generation, born into the runo song culture, who had learnt their knowledge and skills by ear. Other musicians belonged to a younger generation who had gone through the primary education of the time: people who knew their parents’ tradition but were also a part of the new literary culture and the new musical culture it brought along with it. This division is evident in the recorded tunes: they include sung runo songs as well as the popular folk tunes of the time, and in addition to the dance tunes mentioned above, the instrumental music contains runo tunes, a few shepherd tunes (in the notes taken by Armas Launis), and obvious improvisations and church bell tunes.

”Ei sua tiedeä, kudamis kielis olis syytä” (-”One can’t find out which strings are wrongly tuned”)

The core of the whole archaic kantele tradition is in its singular playing technique: the scale is constructed by alternating the fingers of both hands with different fingering options using the technique known as “sormet sormien lomahan”, ‘fingers among fingers’. The strings are plucked into the air and are allowed to vibrate freely until the vibration ends by itself or until they are plucked again. Thus, even though the musician might only play one string at a time (for instance, a monophonic melody), the resulting web of sound is extremely complex: all of the previously played notes continue to ring, slowly fading, and yet – through resonance – also creating new frequencies. And of course, the musician usually does not merely play monophonically but has fun with different interval combinations.

An essential factor in the music and the resulting aural image is also how the instrument is tuned. As mentioned, Väisänen did not record merely tunes from musicians; he also understood that in order to document all of the essential parts of the tradition, he needed to include matters such as how and in what kind of scale each musician tuned their instruments. Previously, kanteles were made by the musicians themselves by carving them out of a single piece of wood. This means that each instrument was unique and that the tuning level varied depending on the instrument’s structure. When the key levels of the strings (partial frequencies) approach the natural resonance frequencies of the wood/sound board, the sound board is quick to react. As the sound board resonates on the frequencies created by the notes of the strings, with its resonance it also moves energy back to the strings and thus strengthens their sound.

Figure 1. The tuning method of Teppana Jänis.

Figure 2. Scales used by Karelian kantele players from the early 20th century.

Each instrument was thus a unique individual because of the wood selected for it and the structure of the sound board created as a result of carving it. The musician would then find the right tuning level for this instrument. After choosing the instrument’s tuning level, the musician would choose the key levels or scales. Tuning was accomplished by listening to intervals; fifths and fourths were important, as well as the octave, depending on the size of the instrument. As a result of the tuning being accomplished with these intervals, the scale can naturally accommodate different modes such as Mixolydian, Lydian, and Dorian, as well as the major scale. Väisänen also recorded a neutral sixth and/or third degree from some musicians. This prompts the question: what size were fifths in these instruments?

Figure 3.

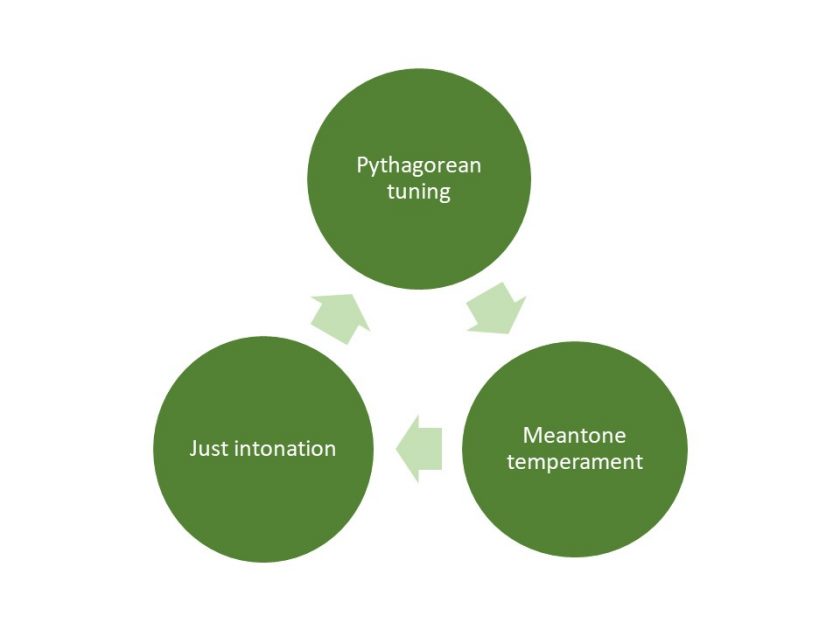

If all fifths are tuned as perfect, this means a Pythagorean tuning method is being used. In the Pythagorean method, the scale includes extremely high major thirds and low minor thirds – the difference is 22 cents compared to the thirds of a just scale – and the octave formed by 12 perfect fifths is 24 cents, i.e. it is one Pythagorean comma broader than a perfect octave. In a just intonation, however, the thirds are formed based on the harmonic overtone series, and their perfect place can thus be determined only for one fundamental frequency at a time. This means that the pitch should be possible to be changed according to the fundamental frequency used, which, however, is not possible in a fixed-pitch instrument. If one considers the diatonic scale in a fixed-pitch instrument, a type of tuning in which all fifths are perfect or all thirds are just is practically impossible. An interesting detail relevant to this discussion is that the older kantele players recorded by Väisänen used only 5 notes, or, in addition to this five-note selection, a fifth-degree lower octave or a diatonic scale without the seventh note in the scale on the top strings.

Of the nature of the archaic kantele tradition

The birth and development of various tuning systems has greatly intrigued me in relation to the tuning of the archaic kantele. The significance of the Pythagorean tuning system is of great historical importance, since it was in use at least from the time of Classical Antiquity and all through the Middle Ages. According to some researchers, the scale bearing Pythagoras’s name was in use already at least a millennium before Pythagoras lived. In her book “Hiljaisuuden syvä ääni” (‘The Deep Voice of Silence’), Hilkka-Liisa Vuori bases her text mainly on the thoughts and teaching of Iégor Reznikoff, according to whom e.g. the theory of scales from Classical Antiquity is based on people listening to overtones. In overtones, everything essential is in a resonance relationship with the fundamental frequency. According to Vuori, it is certain that Gregorian singing included two major thirds: the Pythagorean (81/64) and the just (5/4). (Vuori 1995, 74.)

Here, we must ask a challenging yet essential question: how much can we assume that these scales, based on the culture of Classical Antiquity, were in use in the Baltic Finnish area before the Finnish Middle Ages, or did the scales begin to be used only as the Catholic church gained influence in the 12th–13th centuries? The following is a direct quotation from Hilkka-Liisa Vuori’s text: “According to Reznikoff, the teachings of Pythagoras, the philosophy of Plato — and Orphism are all part of the same tradition, to which ancient Finnish Kalevala-style poetry also belongs. They are part of a chain leading back even further, to older Eurasian shamanistic cultures and sacrificial traditions, c. 1000–2000 BC.” (Vuori 1995, 60.)

Be that as it may, the nature of archaic kantele music is in any case connected to many interesting questions related to the cultures of 1,000 and 2,000 years ago. In Border Karelia, the close connection of runo song culture and the old kantele playing technique (in which the kantele is played with the left and right fingers, with the fingers interlaced when plucking) is evident in the fact that as the runo song culture disappeared from the area, the old style of playing kantele also vanished.

Through cultural change, the kantele became a completely different instrument from an instrument-acoustic point of view – or more precisely, into many different instruments – compared to what it had been in the runo song culture. The kantele carved from a single piece of wood changed into big box kanteles built from several different parts; the playing techniques used in these kanteles are also entirely divergent from the old plucking technique.

Because the strings are plucked upwards in the old plucking technique, and moreover, the strings are mostly not muted at all, the resonance created is incredibly rich. The harmonics of a string plucked into sound move to the sound board and awake the corresponding frequencies in the neighbouring string, which, on their part, are reflected back to the original string. The string continues to resonate in this way, and also the strings that have not been played start to reverberate along with the others due to the resonance (naturally, this also has a cause-and-consequence relationship going in both directions with regard to tuning). In the end, the harmonic series born in the instrument, and the timbre that comes through with it, is thus considerably more complex than the harmonic series formed with merely one string. (Kastinen 2000, 75–78.)

In addition, the sound is accompanied by beating especially in the shortest strings. At one end, the string is tied to a metal bar or a pin with a knot, which leads it directly over the top plate to the tuning peg. Being attached with a knot causes the following effect: when the string begins to vibrate due to being plucked, the string achieves two slightly different vibrating lengths, horizontal and vertical. One of these ends in the knot and the other in the metal bar (or, depending on the manner of construction, the pin). When the two vibrating lengths and their frequency difference come together, the beating characteristic of the carved kantele’s sound is born. And when the string reaches from the metal bar directly to the tuning peg, the tuning peg starts to vibrate as well, and, as it resonates through the sound board, it creates its own flavour in the mix of wavering frequencies. (Karjalainen – Backman – Pölkki 1993.)

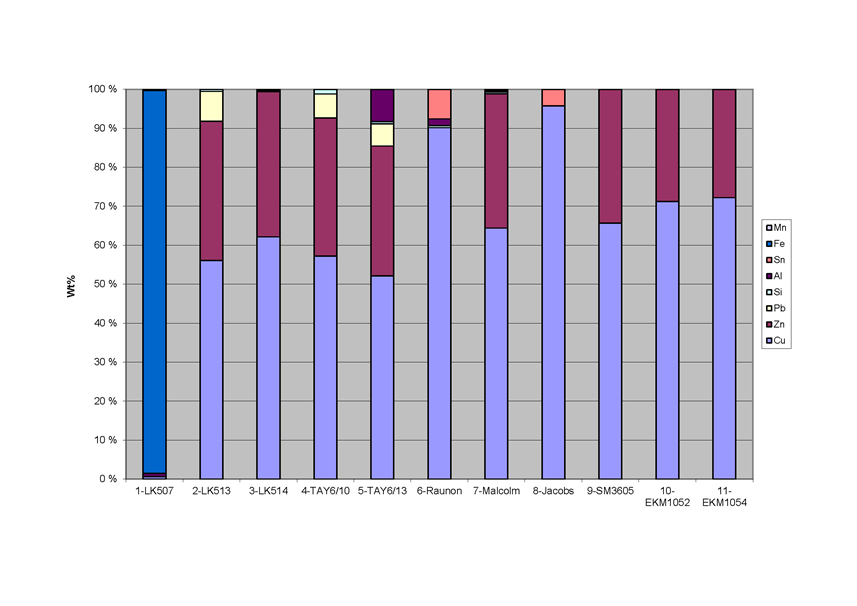

In addition to the structure and material of the sound board, one essential factor in how a string instrument’s sound is constructed is the material that is used for the string. When I was working on the book Kizavirzi, I searched in museums for possible instruments that could be linked to Karelian kantele players, so that Rauno Nieminen could perform a more detailed instrument examination. Only at that point did I understand that in the 18th century and before, the predominant string material for carved kanteles was vaski. Vaski is the oldest name for metal in the Uralic languages, and in Finnish it means a copper alloy metal; in this context, the most common are brass (copper + zinc) and bronze (copper + tin). I was allowed to take a string sample of some of the museum instruments; I sent these samples to be analysed in the Department of Materials of the Tampere University of Technology. Of the eight museum kantele string samples analysed, seven were brass, in which there might be small amounts of other metals in addition to copper and zinc. One of the strings was mainly iron, which included a small amount of copper as well as aluminium and manganese. (Kastinen 2013, 277–279.)

Figure 4. The string analysis.

Old time kantele builders could also make strings themselves – evidence of this can be found in e.g. a humorous newspaper column written by Pietari Päivärinta from the end of the 19th century. In this column, he describes how the string used in catching hares was pulled through the differently sized holes of a specialised metal implement known as a vetorauta, as a result of which strings of different thicknesses could be created. (Laitinen 2010a, 126.) This kind of vetorauta was found in the remains of a smithy at an archaeological dig led by Svetlana Ivanovna Kočkurkina in 1978–1980, in Paasonvuori in Sortavala. This iron, which had holes punctured into it, was made from a broken scythe blade and has been dated to the 12th–13th centuries. (Kočkurkina 1995.)

How far does the history of the kantele reach?

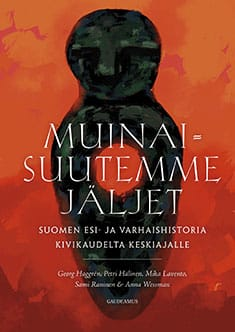

In 2016, the first archaeological general reference book to cover all of Finland was published: Muinaisuutemme jäljet. Suomen esi- ja varhaishistoria kivikaudelta keskiajalle (‘The Signs of our Antiquity: Finland’s Prehistory and Early History from the Stone Age to the Middle Ages’). This book provides a tremendously interesting journey along the millennia and beyond. Below, I have excerpted a few details from this book; they are also partly related to the history of the kantele.

Archaeological findings show that the skill of pulling brass string was known in Finland at least by the Viking Age: in the sumptuary decorations of funeral finds from that time, there are spirals made from thread of copper alloy. Even though men’s artefacts have more of an emphasis on international, far-off contacts, and women’s artefacts emphasise the local area and their own ethnic background, the spiral patterns can be found in clothes for both. This usage is a unifying Southern Finnish feature, as opposed to the denizens of neighbouring areas overseas. In the Viking Age, men’s clothes and jewellery have clear connections to Central Sweden, Gotland, and the Eastern Baltic region. Although the majority of jewellery made of copper alloy was domestically produced (based on evidence from their design), the materials for the jewellery must have been brought from elsewhere. Bars of copper alloy, made to be used for the production of brass objects, have been found in Köyliö (in South-western Finland) from the Viking Age; at this time, brass, the alloy of copper and zinc, was a very common material for jewellery in Northern Europe. Most of that brass probably originated in Central Europe. (Raninen, & Wessman 2016, 296 ja 331.)

In the Finnish region, bronze started to be used already at the start of the second millennium BCE, and it remained the most important metal for over a thousand years. People in the area learnt to smelt iron in around the 500s–300s BCE. Cultures from different directions seem to have met in Finland’s area already during the Bronze and Early Metal Ages. (Lavento 2016, 211.)

The golden age of the eastern trade was in around 900–950 CE. Settlements began to centre around the north-western coast of Lake Ladoga from the start of the Viking Age. These settlements had roots in the Middle Iron Age and were perhaps additionally populated by settlers from Western Finland. From these Viking Age roots, the Karelian settlement of the age of the Crusades grew; it left behind rather impressive grave sites. This ancient Karelian culture, especially during the age of the Crusades, differed in many ways from the culture of Western Finland. The Karelian area on the north-western side of Lake Ladoga was also clearly differentiated from the south-eastern side of the lake and of Olonets Karelia – the Late Iron Age people of those regions, who built burial mounds, has been connected mainly with the Vepsians. (Raninen & Wessmann 2016, 297, 307 ja 353.)

The contact networks of the people on the north-eastern coast of Lake Ladoga spread over a wide area. Some Karelian artefacts from the age of the Crusades have been found in Western Finland, and conversely, Western Finnish artefacts have been found in Karelia. In Southern Savo (Mikkeli) and in parts of Päijät-Häme (Nastola), there are so many Karelian-type artefact finds that contact between the areas must have been close, or people from around the Ladoga may even have moved to those areas. The artefacts of the Karelians from the age of the Crusades also reveal that they had contacts with Gotland, Estonia, and Ingria. However, the kingdom of Novgorod eventually became the Karelians’ most important neighbour. The relationship seems to have stayed on the level of being allies for a long time, until Novgorod appears to have subjugated the area in the 1270s. On an archaeological level, the influence of Novgorod on crusade-age Karelia can be seen in the shapes of many artefacts, and also as the borrowing of metallurgical techniques. (Raninen & Wessmann 2016, 356 ja 357.)

In Southern Finland, the most visible change happened in the 13th century, when the Catholic church, together with its parish organisation, spread to the area. Southern Finland became a stable part of Western Christendom and the dominion of the Pope in Rome; at the same time, most of Karelia remained under the influence of the eastern church. South-western Finland became integrated as a part of Sweden. (Haggrén 2016, 373.)

The research material produced by archaeology opens up some interesting views in my mind, also with regard to my ponderings about the history of the kantele. Did the kantele reach the Baltic Finnish area only as a result of Novgorod’s influence in the 11th century? This is referred to in studies on kantele-like instruments that have been found in Novgorod-based archaeological digs from around the 11th century. Or was the instrument already in use in Finland’s area already at the start of the Iron Age? In his theory on poetic styles, Matti Kuusi dates runo poems concerning the birth of the kantele to the first millennium CE. An example follows: according to this song’s maker, the birth of the kantele and the music born from it is also the birth of iron, the beginning of a new age.

Sitte vanha Väinämöinen Then old Väinämöinen

Istuvi ilo kivelle, Sat upon a joyous rock,

Laulupaa’elle panihen. Sat himself on a singing stone.

Sormin soitti Väinämöinen, With his fingers Väinämöinen played,

Kielin kantelo pakasi, The kantele spoke with its strings,

Soitti päivän, soitti toisen, He played for one day, he played for another,

Soitti kohta kolmannenki. He played for yet a third.

Ei sitä veessä ollut, There was nothing in the water

Ku ei tullut kuulemahan; That did not come to hear him:

Itsekin veen emäntä The water’s mistress herself

Vetihen vesikivelle, Pulled herself onto a wet rock,

Sinisukkihin sukihen, Pulling up her blue socks,

Punapakloihin panihen, Wearing her red ribbons,

Nousi koivun konkelolle, She climbed up into a birch,

Rinnoin ruoholle rojahti. Fell down upon the grass.

Eipä sitä metsässä ollut There was nothing in the forest

Jaloin neljin juoksevista, Of those that run on four feet,

Kaksin siivin lentävistä, Of those that fly on two wings,

Ku ei tullut kuulemahan. That did not come to listen.

Itsekin metsän isäntä The forest’s master himself

Veäksi vuoren kukkulalle, Came to the mountain-top,

Tuo tuli kanssa kuulemahan Came as well to listen

Soitantoo Väinämöisen, To the playing of Väinämöinen,

Iloitsentoo Ilmarisen. The joyous music of Ilmarinen.

Itse vanhan Väinämöisen Water ran from the eyes

Vesi juoksi silmosista, Of old Väinämöinen himself,

Pyriämmät pyyn munia, Let the more eager gather the eggs of a hazel grouse,

Häriämmät här’än päitä The more bold gather ox’s heads

Karvasille ryntähille, For the hairy chest,

Tinasuulle kukkarolle, For a tin-mouthed purse,

Jal’an juurehen Jumalan. In front of the feet of God.

Siitäkin synty synty, That was the birth,

Siitä synty rauta raukka. That was the birth of poor old iron.

(SKVR VII:1, 625. Ilomantsi.)

Aural image vs. musical notation

Let us return to Väisänen and the kantele tunes he recorded. The matters I mentioned earlier, such as the choice of tuning system and thus the size of intervals, as well as the instrument’s acoustic features emphasised by the playing technique, already cause quite a conflict between the musical notation and the aural image created by the music. In addition, there are issues with interpreting the actual musical notation.

Most of the Karelian kantele players of the older generation whom Väisänen met were illiterate, as mentioned: they could neither read nor write. They had absorbed their kantele playing skills, runo singing, and all the information concerning that culture by ear, and as an orally transmitted tradition. So, can we – people living in this age and culture, which is completely different from theirs – find a way to their music by reading and interpreting it through a tool completely foreign to them, that is, musical notation, and without an aural image of the music? I claim that we cannot. As a comparison: if a musician lacking proper knowledge about jazz music and its styles of musical notation begins to play a jazz tune from sheet music based merely on their own, different musical background, the aural image is very far from how jazz musicians would play it. In this case, would we say that the musical notation was badly written? – No. We would say that the musician does not know how to interpret that notation.

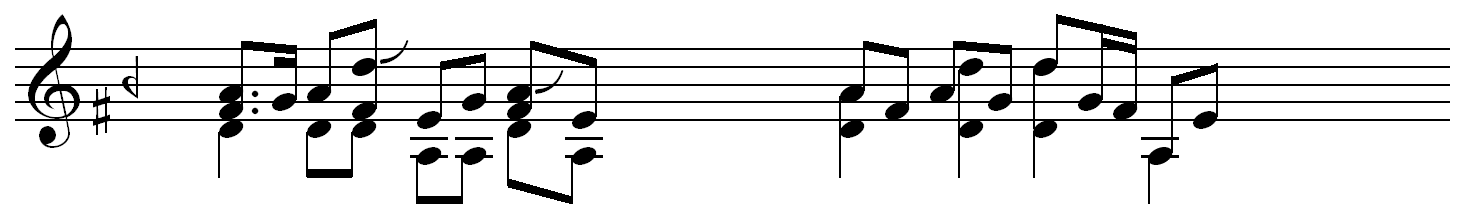

The situation is comparable to the kantele tune notations made by Väisänen. The few old recordings that survive, offering us an aural image, very clearly present the issues with musical notation and the original music. I think Väisänen realised this issue very well. In one of his articles, Väisänen referred to the legendary Jaakko Kulju, writing about how impossible it is to authentically move music that flows on as a constant stream of variations onto a stave. (SKS. KIA. A. O. Väisäsen arkisto. Kantelespel i Kalevala och verkligheten. Manuscript in Finnish.) It is likely that Väisänen did not believe that any musician would attempt to play the tunes he had collected based on the sheet music; the book Kantele and Bowed Lyre Tunes was thus aimed at researchers. It was also not feasible for the book to grow beyond a certain length, so possible variations were recorded as footnotes, which are difficult from a musician’s point of view.

As has been remarked upon many times over the decades, Väisänen was a spectacular notator of music. However, we, who have received our education in this day and age, and being people of this millennium, live on what is almost a different planet from the old Karelian kantele players. This is why Väisänen’s field notes and his own hand-written clean copies of his notations, kept in the archives of the Finnish Literature Society, are an invaluable source of information. These manuscripts include notes and observations interspersed with the sheet music; these are very useful when trying to transform the musical notation back into an aural image.

In the old playing technique, the strings are mainly plucked upwards, and they are only muted in exceptional cases. This means that also those strings that are not played vibrate with the music, making the whole instrument resonate. How long a string resonates (and thus, how long that note is part of the aural image) depends on how strongly the string is plucked, the structure of the kantele, the material of the strings, and the playing technique. All of this cannot be marked in the musical notation without it becoming too complex to be read. The sheet music thus only contains the notes that are played in each moment, not those that are already ringing in the texture as a result of being previously plucked.

In addition, all of the notes are for the most part marked as being similar in strength, which in practice they are not. The music is a polyphonic web from which the musician can lift out certain parts when they wish to. Things that are naturally emphasised in the aural image are often e.g. high notes played with the thumb, strong intervals such as fifths and octaves, and fingernail strikes. In addition to these, the musician can consciously emphasise e.g. the middle notes or build melodic arcs for the lower strings. In a collection of tunes collected by Hällström, from Ladoga Karelia from 1895, there is a description of how Jehkin Iivana, i.e. Iivana Shemeika (1843–1911) played:

The musician creates a sound like a piano pedal thus: he plays (plucks) away from the string with his fingernail, and immediately afterwards presses or gently touches the string with the muscle side of a crooked finger, which creates the same effect as using a sordino would. He can also emphasise the note (melody), whether it be on the bass side or higher up, as he wishes.” (Tenhunen 2013, 74.)

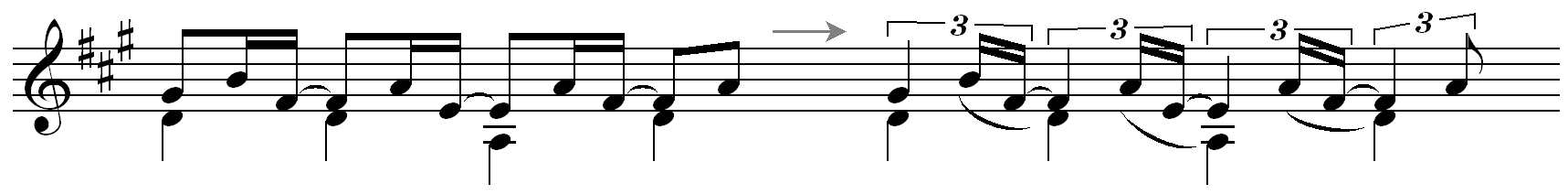

Apart from the fingernail strikes, none of these emphases are usually separately marked in published sheet music. Some of the manuscripts contain indications that the notes emphasised by the musician might possibly have been marked in separate stems and as lasting longer. In the manuscripts Väisänen made clean copies of, he marked notes that were strongly emphasised and ringing in the aural image for a long time with red notes and beams (in the following example, the beams have been converted to short, upward-directed secondary beams).

Figure 5.

The interpretation of the rhythms in musical notation is also worth some thought. Especially in dance tunes, some recordings give evidence of how, e.g. in combinations of two quavers (or a quaver and two semiquavers), the former quaver lengthens a little and the latter shortens. This makes the rhythm more danceable, with more swing. Sometimes the first beat can also be shorter, especially if the second is accented or on the off-beat. It should be obvious that written rhythms should not be interpreted on a metronome’s level of accuracy. Subtly varying the rhythms also often seems to make executing quick rhythmic patterns easier – you get into the swing of the thing, so to speak.

Figure 6.

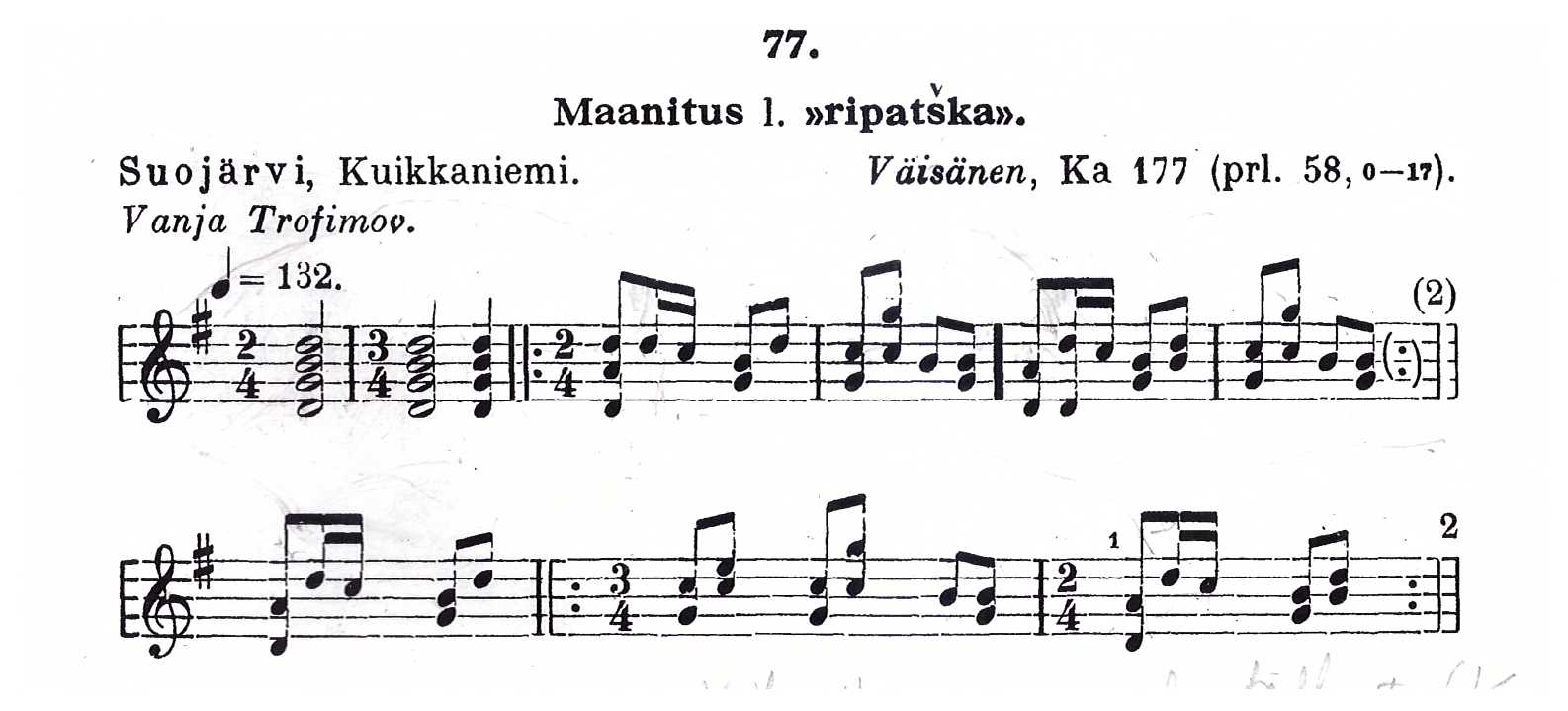

Sometimes the bar line also appears to be situated differently than what the musical notation would first suggest. The clearest example of this is the Maanitus played by Vanja Trofimov (later Tallas), of which there are instantaneous disc and radio recordings which date from later than phonograph recordings. Here is the start of the sheet music published by Väisänen (Väisänen 2002 [1928], 39.):

Figure 7.

The phrases according to the recordings (Kastinen 2013, 135.):

Figure 8.

The power of the word, the power of song, the power of music

It can be seen that the tunes that have been recorded represent only a tiny sliver of the music that the old kantele playing tradition consisted of – in terms of number of tunes as well as in terms of the length of the kantele’s history. However, I believe and hope that through the study of the recorded tunes, information on playing technique and tuning, and general historical research, it will be possible to reach something of that vast musical world, based on improvisation, which the Karelians called the musician’s own power. A skilled singer possessed the power of the word, and a musician possessed the power of music. Even though there are no extant recordings of music that is explicitly named the musician’s own power, all of the textual evidence and descriptions related to the subject lead one to understand that playing one’s own power was as quotidian and natural an action as speaking was – or runo singing.

How a musician touches their instrument has an effect on how the instrument rings. Even small changes in human touch – strength, speed, direction, placement of the touch – affect the construction of the overtone series and thus change the timbre of the note. This is essential, because timbres are a means of telling a story: “With his fingers Väinämöinen played, the kantele spoke with its strings”. (SKVR I:1, 102.) In the words of Heikki Laitinen: “The kantele spoke and sang, told stories. The entire worldview concerning music was very different from our current one.” (Laitinen 2010b, 90.)

The enchantment created by the kantele’s sound has not disappeared during its millennia-long history. At first glance, it seems like a simple instrument; but it also appears to have the quality of seeking to create music by itself. When you begin to play, it is difficult to stop. This instrument still has the power to guide its player into the world of quiet exaltation.

References

Haggrén, Georg 2016: Keskiajan arkeologia. [’Medieval archaeology’] In Muinaisuutemme jäljet. Suomen esi- ja varhaishistoria kivikaudelta keskiajalle. Helsinki: Gaudeamus.

Karjalainen, Matti – Backman, Juha – Pölkki, Jyrki 1993: Analysis, Modeling and Real-time Sound Synthesis of the Kantele, A Traditional Finnish String Instrument. Proc. Int. Conf. on Acoustics, Audio and Signal Processing (ICAASP 1993), vol. 1, Minneapolis, USA.

Kastinen, Arja 2000: Erään 15-kielisen kanteleen akustisesta tutkimuksesta. [’On the acoustic research of a certain 15-string kantele’] Helsinki: publications of the Sibelius Academy’s Department of Folk Music 5.

Kastinen, Arja – Nieminen, Rauno – Tenhunen, Anna-Liisa 2013: Kizavirzi karjalaisesta kanteleperinteestä 1900-luvun alussa. [‘A Song about the Karelian Kantele Tradition at the start of the 20th Century’] Pöytyä: Temps Oy.

Kočkurkina, S. I. 1995: Muinaiskarjalan kaivaukset. [’Excavations in Ancient Karelia’] Arkistojulkaisu 3. Kuopio: Snellman-Instituutti.

Laitinen, Heikki 1980: Karjalainen kanteleensoittotyyli. [’The Karelian kantele playing style’] Kansanmusiikki 2/1980.

Laitinen, Heikki 2010a: Kanteleen historian käännekohtia. [Turning points in the history of the kantele’] In Kantele. Ed. Risto Blomster. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society.

Laitinen, Heikki 2010b: Rakas tunnettu kantele. [’Our dear well-known kantele’] In Kantele. Ed. Risto Blomster. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society.

Lavento, Mika 2016: Pronssi- ja varhaismetallikausi. [’The Bronze and Early Metal Age’] In Muinaisuutemme jäljet. Suomen esi- ja varhaishistoria kivikaudelta keskiajalle. Helsinki: Gaudeamus.

Timonen, Senni 2011: A. O. Väisäsen tutkimusmatkat Raja-Karjalaan 1916–1917. [’A. O. Väisäinen’s field trips to Karelia 1916–1917’] In Taide, tiede, tulkinta. kirjoituksia A. O. Väisäsestä. [’Art, Science, and Interpretation: Writings on A. O. Väisänen’] Ed. Ulla Piela, Seppo Knuuttila, and Risto Blomster. Kalevalaseuran vuosikirja [’Karelian Society Annual’] 90. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society.

Pulkkinen, Asko 1946: Suomalaisia kansantanhuja. [’Finnish Folk Dances’] Porvoo: WSOY.

Raninen, Sami & Wessman, Anna 2016: Rautakausi. [’The Iron Age’] In Muinaisuutemme jäljet. Suomen esi- ja varhaishistoria kivikaudelta keskiajalle. Helsinki: Gaudeamus.

Tenhunen, Anna-Liisa 2013: Henkilökuvat. Iivana Shemeikka. [’Portraits. Iivana Shemeikka’] In Kizavirzi karjalaisesta kanteleperinteestä 1900-luvun alussa. Pöytyä: Temps Oy.

Vuori, Hilkka-Liisa 1995: Hiljaisuuden syvä ääni. [’The Deep Voice of Silence’] Helsinki: Kriittinen korkeakoulu.

Väisänen, A. O. 2002: Suomen Kansan Sävelmiä, Viides jakso. Kantele- ja jouhikkosävelmiä. Johdannon kirjoittanut ja sävelmät julkaissut A. O. Väisänen. [’Finnish Folk Tunes V: Kantele and Bowed Lyre Tunes. Introduction written and tunes published by A. O. Väisänen’] Second edition. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society.