Ogoi’s Song Had It All

Blog

June 29, 2021

Photo: Hiromi Hokkanen.

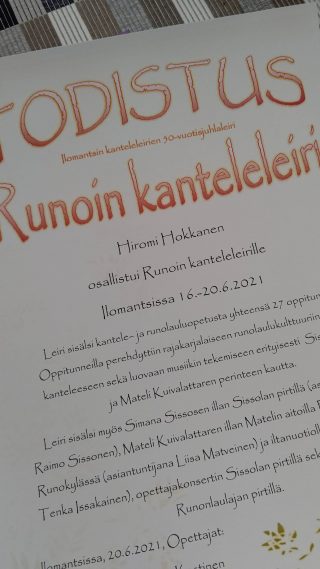

Runoi’s kantele camp (June 16–20) is over and I’m still digesting it. Planning and making preparations took almost a year. There were many twists and turns of which the covid-19 was not the smallest one. And finally, everything condensed into five hectic days.

Digesting haven’t been merely mental: the meals at the inn PikkuPriha were absolutely delicious. Warm thanks to Elina and Vesa!

The meals at the inn Pikkupriha! Photo: Hiromi Hokkanen.

The seed idea of the camp was to celebrate the 50th summer from the very first kantele camp in Ilomantsi, on which I got my first contact with the kantele.

For some time I had also had a vague dream of a course which would concentrate on the kantele of the runosong culture. And so it happened that a year ago, right after my lecture concert at the Sissola, the first words for organizing this camp were spoken with Irma Väisänen and Jaakko Hamunen, the secretary and the chairman of The Contributional Society of Sissola.

The courtyard of Sissola. Photo: Hiromi Hokkanen.

The home of Simana Sissonen (1786–1848), the Sissola, is the only runosinger’s courtyard in Finland that is still situated in its original place. Since this year marks the 235th anniversary of Simana Sissonen’s birth, and the 250th anniversary of the birth of Mateli Kuivalatar, it was quite obvious to choose their songs as the core material of this camp.

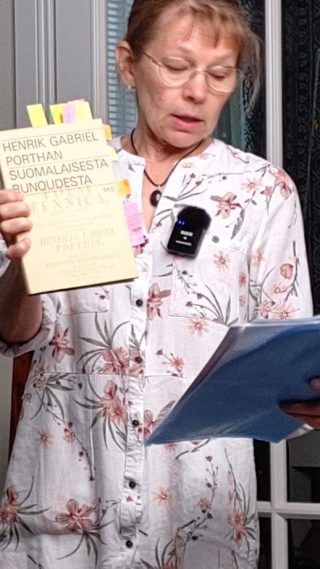

Liisa Matveinen. Photo: Hiromi Hokkanen.

The wonderful singer Liisa Matveinen was teaching the runosong.

Since the Kantele-Go! -project in Russian Karelia asked for the possibility to participate the course online, we organized live streaming. The video recordings are found here. A HUGE THANKS to Jarmo Romppanen and his Videotuotanto Vauhtiluiska Oy for the dedicated work.

Jarmo Romppanen. Photo: Elina Haavisto.

To come true, the big dream needed also external financiers whom we can not thank enough: The Finnish Cultural Foundation’s North Karelia Regional Fund, The Kalevala Society, The Adult Education Centre of Ilomantsi, MES and The Cultural Association of Rantalan Virta.

How does the Ogoi’s song mentioned in the title relate to all this? -Deeply and in every way. For several decades I have studied the old kantele recordings at the archives of the Finnish Literature Society. In addition to the wax cylinder recordings from the beginning of the 20th century they also have, for example, the copies of the tape recorder recordings made by Fritz Bose in 1936.

By chance I bumped into one special runosong among them this spring. The runosong Kullervon sotaanlähtö [sksa20110054h] sung by Ogoi Määränen was and is stunning.

First of all, one can realize the incredible conflict between the singing and the sheet music. Actually, there is no published sheet music from this particular performance, but if we compare it to the published short runosong melodies (esavelmat.jyu.fi), the huge difference between them becomes relevant and is quite confusing. The same applies to old kantele recordings: sheet music is not able to picture the reality of the diversity, the variability, the livelyness, the soul of the improvised music by illiterate people.

Sissolan pirtissä. Kuva: Hiromi Hokkanen.

Second, also confusing, the strong fading of the boundary between phrases. At some points, for example, Ogoi binds the words together, and I had big difficulties to learn to understand what was happening in the music and what she was actually singing.

Third, adding wonderful ornaments and varying the melody constantly – including different sizes of thirds.

Fourth, combining phrases with different lengths: as the basic beat goes in 5/8, every now and then Ogoi terminates the phrase in 6/8 “bar”. In addition, twice – the same text each time – she sings 9/8 + 6/8.

And fifth, the change of the metre in the middle of singing: in the dramatic part of the song, when Kullervo is told that his fiancée is dying, Ogoi starts to sing in 5/4 and continues that way until to the end.

All the elements mentioned here have been and are being used when teaching the tradition of the old plucking technique of the kantele. I just hadn’t found this complete example earlier – Ogoi’s song has it all.

Before the camp I had a correspondence with Professor Emeritus Heikki Laitinen and received lots of valuable information concerning the topic and the archive material related, for example.

In one of his articles (Kantele -book, p 89–90) Laitinen describes the union between the runosong and the old kantele: ”Singing had a special power but as the kantele songs show, so had the kantele music as well… Kantele was talking and singing, telling stories. The whole spirit about music was very different from ours today.”

In many of the runosongs about the mythical birth of the kantele there is a phrase describing how the kantele is talking. In Simana Sissonen’s songs the phrase goes like this: “kielin kantele pakisi” – the kantele spoke the language. (It is fascinating that the word “kieli” in Finnish language means both the tongue and the language – and also the string of an instrument!) Laitinen writes: “The power in playing the kantele is in its ability to describe and take over the world around you”.

Some information about the tradition at the beginning of the first kantele lesson. Photo: Hiromi Hokkanen.

As, for example, Senni Timonen wrote in her doctoral theses (Minä, tila, tunne. Helsinki, 2004) in runosinging we have the so called singing language. Elias Lönnrot wrote in 1840 that in the runosongs the word and the music are like sisters – meaning that they are equal. Eliel Vartiainen described in 1923 in his book about the family Shemeikka how the famous runosinger and kantele player Iivana Shemeikka was talking and singing (and playing the kantele) at the same time when telling a story to children: “the old man is singing a fairy tale”.

Could it have been that the runosong culture is one of those music cultures in which the word “music” is not used? At least in the collected songs (the SKVR, Suomen Kansan Vanhat Runot – The Ancient Poems of the Finnish People – which contains about 90 000 songs) the word is not found.

The music was so inseparable and self-evident part of everyday life that there was no need to categorize it with a separate concept. Everyone learned the singing language together with their mother tongue, and everyone also sang.

Heikki Laitinen writes (Kansanmusiikki -book p. 18) how with improvised fleeting seconds the runosinger builds up an ever-changing microcosmos, which, however, is based on the aesthetics of an infinite continuum. The continuum of phrases without separate stanzas create a space without the beginning or the end. This applies the kantele music as well.

This way of making music was the base of the Runoi’s Kantele Camp.

The five books containing the runosong texts collected from Border and North Karelia

The focus of the playing technique was on the old plucking technique since not a single strumming technique example has ever been recorded from this area.

For the runosong texts we were able to use both the physical books containing the collected songs from this area and the online version of the SKVR.

Also for the runosong melodies we had both the physical book (Suomen Kansan Sävelmiä IV, osa II, published in 1930) and the online version of it.

In addition to learning texts and music, we also listened to some archive recordings.

Raisa Vennamo – an authentic performance of one’s own power. Photo: Hiromi Hokkanen.

From their musical background the participants varied from the beginners to the professionals. However, in this case the background has no meaning since according to the aesthetics of the runosong culture everyone is able to create and live this music from his/her own starting point.

The participants were incredible. They made amazing own runosongs as well as kantele improvisations. In just five days they were able to adopt the aesthetics profoundly. I am so proud and happy for each one of them!

The final concert is about to start. Photo: Hiromi Hokkanen.